We have all witnessed something like this:

- a toddler tantrums in the grocery aisle when refused a sugary treat

- a child screams when his favorite toy goes missing

- a pleasant teenager becomes belligerent the instant she can’t find her hairbrush

These emotional outbursts are often way out of proportion to any recent event. What looks like something small to an adult can feel like a catastrophic threat to a child who is reacting with his survival response – or in his Baby Self.

The Baby Self is there at birth – helpless, unaffected by consequences, seeking nurturing, and demanding attention. Big emotions create chaos when it doesn’t get its way.

Danger! Fear! Survival!

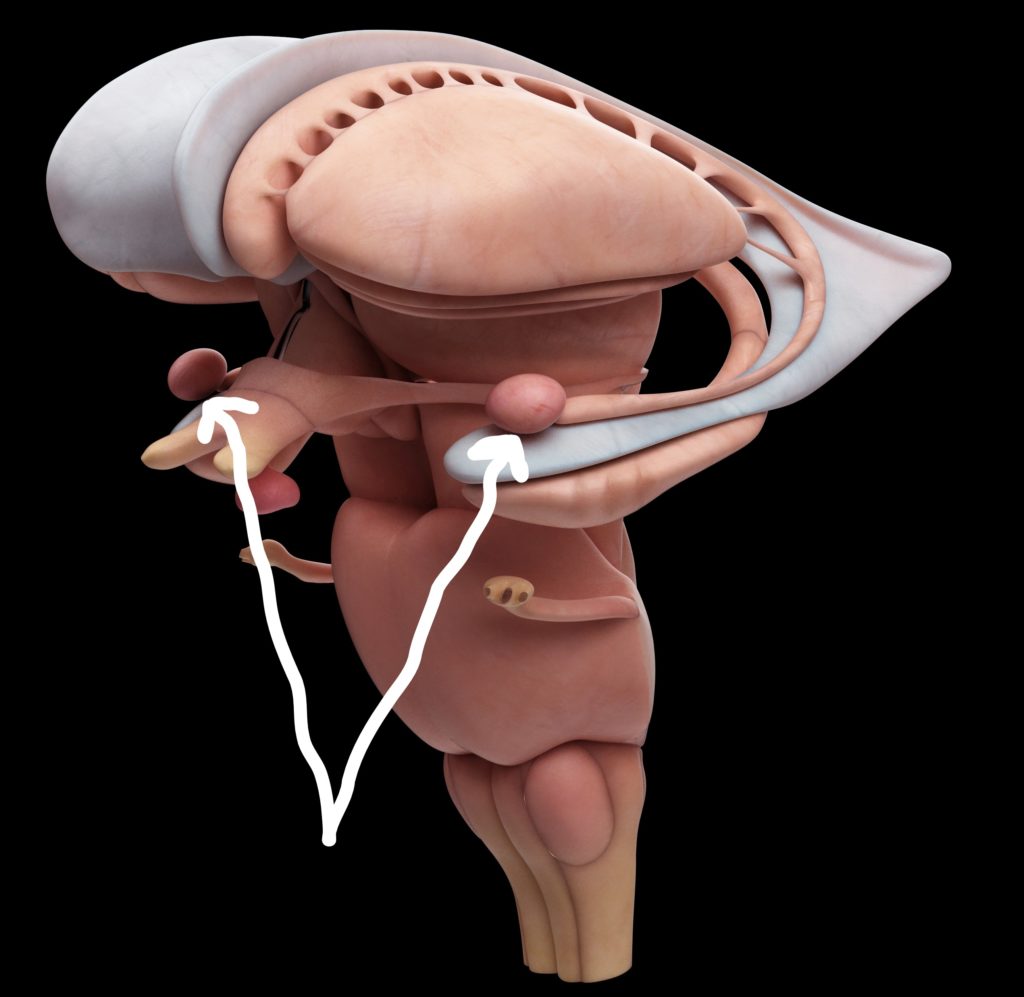

Deep within the brain lies the amygdala, two almond-shaped groups of nuclei. The amygdala are the trigger points for the fight or flight response. They look like two little seats on either side of the brain stem. This is the place where the Baby Self likes to lounge.

When a threat is perceived, circuitry in the brain prepares for an emergency by flooding the body with stress hormones. In fight or flight, blood shunts away from the organs to the limbs and movement occurs. Logical reasoning gets kicked out the door and the Baby Self gives a knee-jerk emotional response.

This amygdala take-over is an ancient reaction developed when a situation was urgent – for example, “Do I eat it or does it eat me?”

Today there aren’t large beasts trying to eat us, so our brains have added a cognitive response. Attention tends to fixate on what is stressing us out, what we’re worried about, or what’s upsetting, frustrating, or angering us.

Neurons of the prefrontal cortex help with rational control over our emotions and help to lessen this response as we grow. Unfortunately for parents, this part of the brain does not mature until early adulthood. Yet the amygdala is mature at birth!

When a child has a tantrum or meltdown, the closest adult would like to break through into the rational part of the brain and reason with the Baby Self. The child’s immature responses are developmentally right on track though, as logic is unable to penetrate through the hormones bombarding the body.

The threat may be symbolic – He took my toy– but a child’s response is huge. In other words, the Baby Self kidnaps the present, but undeveloped, Mature Self in a millisecond if threatened.

Empathize vs. Minimize

An accepted cultural response to a child’s big emotion is to minimize it. The goal is often to get him to change his behavior or feel something differently.

- The child takes a tumble and cries. The parent says, “Oh, you’re alright.”

- A child is upset when she finds her doll has been moved. “Don’t cry. That’s such a little thing.”

- One child takes another’s toy. “Get over it. It’s just a bunny.”

- “Now, now, don’t cry.” The goal is empathy but the effect is shut-down.

Empathize. A 3Rs parent (Respectful, Responsible, Reliable) resists minimizing the child’s emotional expression. Aware that suppressed emotions will find a way to surface later, these parents are not afraid of their children’s negative emotions. They teach their children even though not all actions are allowable, all emotions are okay.

When faced with big emotions, the parent’s 3Rs Self can respond with support and empathy.

- “Is there any more cry?

- “You didn’t like that.”

- “How can I help you wind down?”

- “Tell me again about the upsetting event.”

- “Ohhhhh” or “I see”.

Mobilize

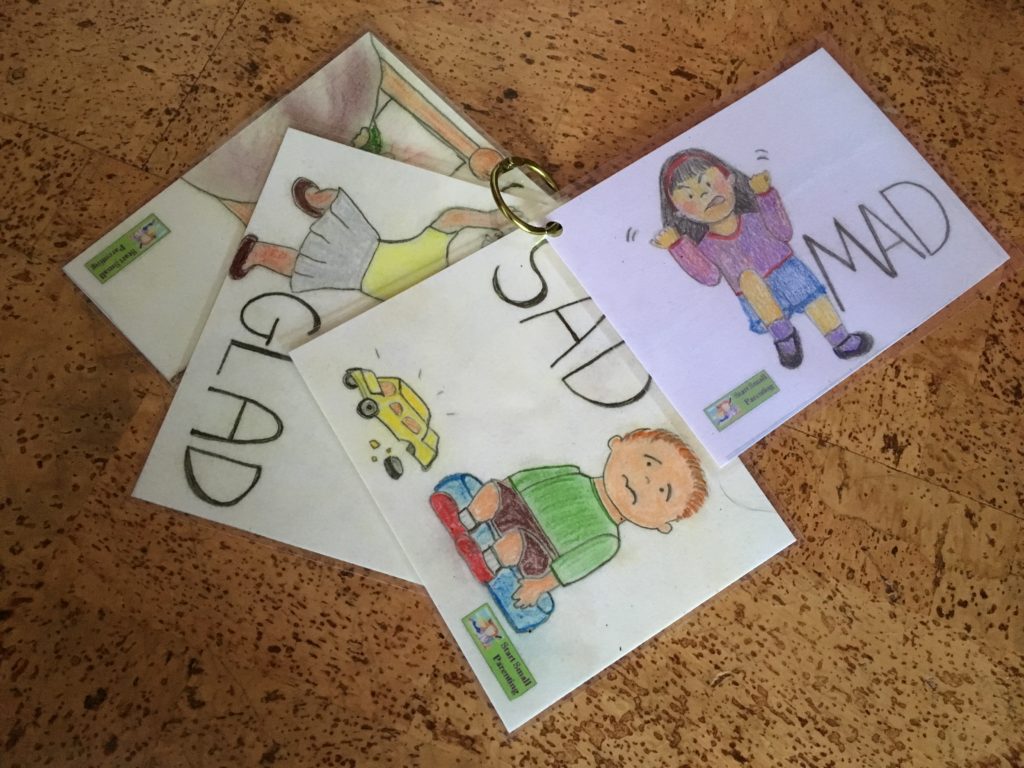

What’s Going on Inside? Teach your child to identify emotions. Use pictures she can retrieve from another room (moving the body moves emotions) to show you how she feels. Often, young children’s big emotions come from frustration at not being understood. Your child can learn to ask for what she wants instead of cry, scream, beg or whine. Help her use words, sign language, act-it-out, or point to pictures to describe what’s going on inside.

Whiteboard Session. In calm moments, the parent and child can come up with ways to move big emotions through their bodies. Brainstorm ideas together. Write or draw ideas on a whiteboard – even crazy, outrageous ones.

For example: hop on one foot; squeeze a pillow; take 5 deep breaths; receive a hug; fly to the moon; stomp up and down the porch steps; eat a banana; get your lovey to hold; hide under a blanket; jump on the trampoline.

Together, pick two workable ones that you and your child can use that week when an anger snap appears or a disappointment triggers a big emotion. If your child is under 5, pictures instead of words are helpful. Revisit the board during the day. Practice together as you play with a pretend big emotion like anger. Use one of the solutions on the board when not struggling with an actual event.

You cannot and should not try to stop your child’s emotions. What you can do is help him during calm moments to learn other developmentally appropriate ways to ask for what he wants, work through disappointments, and self-regulate big or scary emotions from the inside out.