How can we light up children’s brains so they most easily learn? How does better understanding their development increase our connection together?

The Young Brain

Sometimes young children seem like a different species entirely from the adults who parent them. Conflict can occur just because the two people involved see the world very differently. This is partly due to the way the brain develops. The small child’s brain develops preferences of the “Right Brain” earlier than the more logical left. It’s helpful to know what those preferences are so that parents can better communicate with and more easily teach their child.

The Right Brain likes pictures. The Left Brain like lists. This article takes a specific look at what Right and Left Brain preferences are so you can help your child wherever they might be stuck.

The Right Brain likes…

Knowing how the brain develops, we can see that the right brain tendencies are more easily accessed in young children than the more linear left brain. The refined logic of the left brain develops more slowly.

The right brain tendencies are imaginative, intuitive, and emotional. The Right Brain likes pictures. Mostly non-verbal and experiential, the big picture is important as are relationships. It comes alive through art, creativity, music, movement, and colors. Keep this in mind as we look at a variety of suggestions to “talk” to this part of the brain without words.

Movement

Engage your child with movement. If you can get your child to move their body, they can often move their emotions, too. When a child is tantruming on the floor, they very rarely lie still. They kick and pound or roll around. If possible, channel the energy into action: jumping jacks, trampoline, twirl a scarf, run around the kitchen, pushing the wall, etc. This will help the stress hormones move along more quickly.

Music

Music is an incredible parenting tool. Use a favorite song to sing good-bye when you leave the park, directions to get in the car seat, or making a diaper change more bearable. (Plus, it’s hard to be angry or frustrated when YOU sing.) While it calms you, music will also calm your child. This is an all-around win!

Hugs

A hug or some kind of loving touch is one of the best ways to connect in with your child’s right brain.

Smell a flower. Blow a Bubble.

Slow, deep breaths in through nose, as if there is a flower on the end of your index finger. Then hold an imaginary bubble wand to lips. Blow out through pursed lips slowly and evenly as if trying to whistle. Repeat several times.

Draw it Out

Draw out what you want to communicate to your small child. Children as young as 18 months can understand that you are trying to show them something using a picture. For example, draw an unwanted behavior. Next to it draw a desired behavior. I’m not suggesting you need to literally draw the picture. That might not be your skill set. But truly, stick figures will do as will printed out Google images or photos of your child doing what you are trying to convey. Present the images to the child when they are calm. Use a few words to describe the next step you would like them to take.

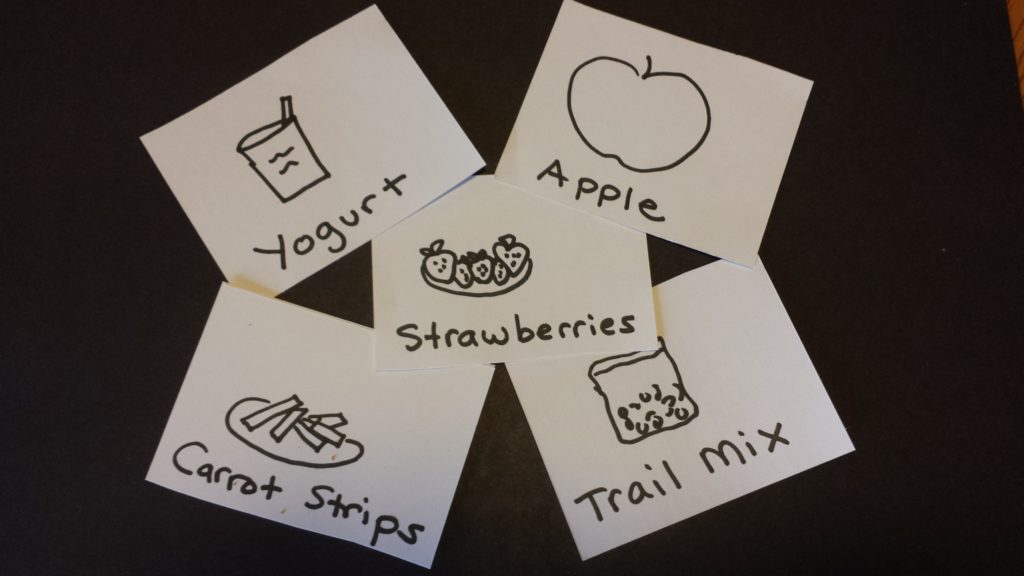

One mother was having trouble warding off the continual snack requests she received throughout the day, especially for sweet treats like yogurt. She made snack cards and gave them to her son. He could turn in a snack card throughout the day but there was only one of each snack he could choose. The visuals helped him have a tangible understanding of what the mother wanted him to learn.

Sign Language

If the right brain likes pictures, then sign language is a great step between actual images and words. Learn some basic sign language for common concepts or expectations you have. Milk, Sleepy, Hungry, Potty, More, All done, and Stop are especially useful. Use them often. This can decrease communication frustrations because children can usually sign before they can talk. My son learned the sign for “milk” at 7 months and “potty” at 9 months. He made crude approximations but we could better understand him well before verbal language came in.

Name It Visually

When you name a feeling, you bring it out into the open. Feelings are just that –something you feel in your body. We name it so we can cognitively understand it.

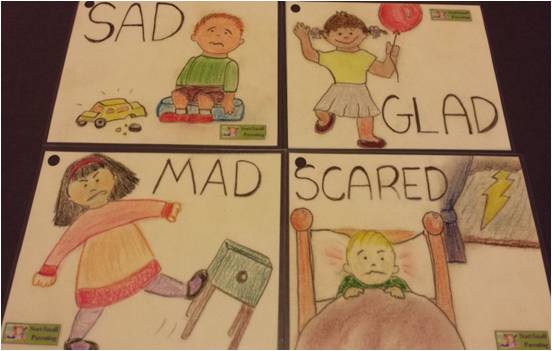

You can also use emotion cards to help children describe what they are feeling and help bring in more of the right brain. These are cards with a word and picture depicting that emotion on each card.

When children are pre-verbal, it’s great to introduce the main emotions of mad, sad, glad, and scared. But don’t shy away from increasing a child’s exposure to more varied feeling-state vocabulary. Angry is different than frustrated. Content is different than relaxed. The more you model naming the nuances of emotion, the more skilled your children will become at describing them.

You can make your own emotion cards or find some on the internet. One mother made these Lollipop Faces – mad, sad, glad – for her 3-year-old daughter. If her daughter was feeling a big emotion, the mom would ask her to go get the Lollipop Faces. Moving her body to go get them helped to move the emotions as well. Then she was able to more easily bring in some left brain reasoning, willing to engage with an idea or solution to the problem.

Another way of describing an emotion is to give it an identity. Here are some examples from families I’ve worked with:

- Anger (The Claw)

- Power (The Tiger)

- Frustration (The Ant)

- Crazy (The Monkey)

- Shy (The Snake)

The Left Brain likes…

The land of the left brain is order and logic. Yes, it prefers lists. It’s also the preference to organize, categorize, strategize, and play with numbers. It is the scientist and mathematician. It is accurate, linear, in control, and analytical. It is a master of words and language. Here are some ways to engage with the Left Brain.

Make a List

When you’re looking to problem-solve, brainstorm together and make a list of ideas. A white board is really useful for brainstorming. All ideas at this point are okay. Allow your child to bring in their own solutions. Encourage your child with your body, words, and tone. Let him know you believe in his growing abilities to help with problem-solving. “I trust you.” “You have my support.” “What are your ideas?” “What can I do to help right now?” “That’s it!”

Ask stimulating questions:

“What can we do when we get angry?”

“What is jealousy telling you?”

“Can you move your frustration another way?”

“What will calm you when you’re frustrated?”

Write each idea down – you could even draw a picture of an idea. Crude drawings work fine. Children are somehow able to understand symbols even if the drawing isn’t close to a real life depiction.

Accept your child’s ideas, no matter how impractical. Children love being included. Perhaps you’ll come up with ten ideas together. Remember to put them all down. Together, narrow it to a few choices. Two is an easy number. Here’s where you can steer the choices to ones you can help with or agree to. Keep those pictures (or words) up as reminders for next time the big emotions surface.

Rephrase

For nonverbal kids, give words to a feeling through suggestion or ask in a way that the child can answer easily. Parent: “You don’t want to leave the park, do you? You’re sad to say bye to your friends. Does it upset you to go?”

With older kids who have verbal skills let them voice their feelings. Mirror back what you hear.

Child: I don’t want to go!

Parent: “You don’t want to go. You’re having fun. It’s hard to leave your friends.”

Naming and rephrasing puts the parent in a witness role, able to acknowledge and allow what is present to exist without judgment. There is no “good or bad” attached to the observations.

Retell

When children have an opportunity to relive an unpleasant or painful event, there is a greater chance that it will pass through as a memory, rather than lodge as a fear or repressed emotion.

Let’s look at the example of my son’s skinned knees. He was almost four when he fell while running after a dog at the park. He didn’t see the parking divider curb and went flying face first onto concrete. Both knees were quite raw.

I gave my son empathy and helped him clean the wounds. Then together, we retold the story – of the big brown dog who wanted my son to chase him, to running as fast as he could over the grass, to being surprised by the fall and the parking block that seemed to come out of nowhere, to losing sight of the dog. There was a lot of disappointment within the story as well as surprise. And his knees really hurt. We named the difficult emotion, which turned out to be confusion and betrayal. Bringing the emotion to light engages the right brain. Giving it a name as well as bringing order by telling the story several more times engages the left brain. Finally, my son was done telling it. He felt much better. He wanted to go back to the playground.

Sometimes the opportunity presents itself to talk about an event right after it happens. Other times, the retelling happens at a later date. When a tree crashed through the roof of my friend’s house as they all sat in the living room, she didn’t have a chance to work through it with her kids until later. The emergency was too big and that had to be handled right away.

If the event can’t be processed right away, try talking about it later while engaged in a fun or calming activity like drawing, Legos, hiking, etc. Let it be a casual unfolding and take your child’s cues as to how much of the story needs to be told. Make sure to name the scary feeling which includes the emotion (right brain) and bring order by giving words to the experience (left brain.)

Name It Verbally

Enrich your child’s vocabulary with more refined emotions. The left brain likes words and language. Words make up our world. Refining and discerning emotions through words helps children grow a greater emotional landscape. Expand your emotional vocabulary as a family. Talk about emotions in Family Meetings or Tell a Story.

Ask questions to help the curious detective in you find out what is going on with your child. Suggest the feeling for them if they are unable. “Were you scared?” or “You look scared.” “Where do you feel that in your body? “Did that hurt you?” “Is that shadow scaring you?”

If you or your child is not comfortable talking about the emotional world, know that it still exists. You can practice going in a side door with your child instead of approaching this head on. Side-by-side can be the preferred formation as you bring another activity into the mix. While taking a hike, planting a garden, repairing a leak, baking cookies – you can bring up an event and ask how the child felt about it. Even if they aren’t able to articulate their response or they don’t want to, asking the question prompts them to think about the event. This opportunity may be just the chance they need to move the emotion up and out of their system.

A Balance of the Two

Tell a Personal Story

Think back into the vaults of your own childhood and life experiences. Find a story that you can share with your child where you had a similar emotion or experience. They will be fascinated by your past and calmed by the feeling that they are not alone in their big experience.

Tell a Customized Story

Create an ongoing, customized bedtime story using animal characters. Children are more often receptive when they are calm and the day is winding down.

One parent I know said that she was a terrible storyteller. She could never think of anything to add to make the story interesting. In Tell a Story, the pressure’s off. Tie in any events of the day that happened to your child or any recent activities or events in your family – only they happen in an animal’s world.

I live where there is a forest and lots of squirrels. One day, my son was having trouble at preschool. I came up with a character called “Squirrel Friend”. Over time, the story evolved to include the squirrel’s best friends, who all represented aspects of my son’s personality. They lived in Squirrel Village and everything they had was made out of what was found in the forest. Acorns, tree bark, leaves, etc. made up food and dishes and clothing. Sometimes my son made suggestions or additions to the story. If the story was too close to his real life experience he would laugh and say, “That didn’t happen to Squirrel Friend. It happened to me.”

If telling a story leaves you coming up blank, here is an exercise from theater improvisation you can use:

Once Upon a Time…

Every day…

Until one day…

And then…

And then…

And then…

Finally…

Another way to use Tell a Story is with actual visuals. You can use puppets, a felt board, dolls, or even objects like rocks. Any object works that helps the child represent their inner world on the outside of themselves. Tell a Story also relaxes a child, helps her work through emotional issues, solve problems, and integrate both sides of the brain.

Read a Story

Find a book with a similar theme that your child is working through. My son had a period of time where he was afraid of the dark. In Franklin in the Dark, by Paulette Bourgeois, a turtle is afraid of small dark places, including the space inside his shell. He asks several animals for advice and finds out they are all afraid of something. This helped my son to see that he was not alone with his fear.

Increased Connections

With a better idea of how your child learns, you can shift the way you introduce an idea or how you teach a new behavior. Frustrations and conflicts lessen. As you child feels more understood and opportunities to join together increase, so does the emotional connection.

|